Carol Dyhouse is the author of Girl Trouble: Panic and Progress in the History of Young Women, a book which, essentially, could be called a history of unladylike behaviour. Ranging from the Suffragists to Kate Moss with the all smoking, all-dancing, scandalously dressed ‘brazen flappers’ and Courtney Love falling somewhere in-between, Girl Trouble is a 20th century history of girlhood that packs a punch. Here we chat to Carol about feminism and female fuckups.

How would you describe ‘Girl Trouble’ and what prompted you to write it?

Girls are often seen as in trouble or as causing trouble. I wanted to focus on the trouble that society makes for girls. And to try to work out whether things have got better or worse.

It’s an interesting choice to use ‘girl’ interchangeably with ‘young woman.’ As someone who uses ‘lad’ a lot it personally doesn’t really bother me (perhaps a Northern thing?) but it grates on a lot of feminists. What is your view on this?

I know that some feminists have seen it as belittling to refer to young women as girls. But I think things shifted with discussion of ‘girl power’ in the 1990s.

The age at which girls are considered grown up has changed through history. In Victorian times a middle class girl was thought to become a ‘young lady’ when she began to menstruate. She would then ‘put up her hair’. These days girls menstruate at younger ages and the hair thing doesn’t apply any more.

Did you feel it was time that young women’s role in history be reappraised and if so, why?

Yes! I wanted to show how attitudes to young women are central to our understanding of social history and to ideas about ‘progress’. Also, to show young women as resourceful, competent beings who have battled to make their own history.

You say in ‘Girl Trouble’ that young women are often painted as the victims of progress rather than the beneficiaries of it. Do you agree with recent comments in the Telegraph that modern feminism has ‘a victim complex’?

The accusation that feminism portrays women as victims isn’t new – it’s something that feminists have always had to wrestle with. There are clearly cases where girls are in danger of being victims – of misogyny, of sexual violence, or of internet abuse. But the whole point of feminism is to fight back and to refuse victimhood.

Your book is full of girls being castigated for ‘behaving badly’. What is it about young women that gets people’s backs up?

A lot of things! Making a noise, taking up space. Some people get upset when girls do better than boys educationally.

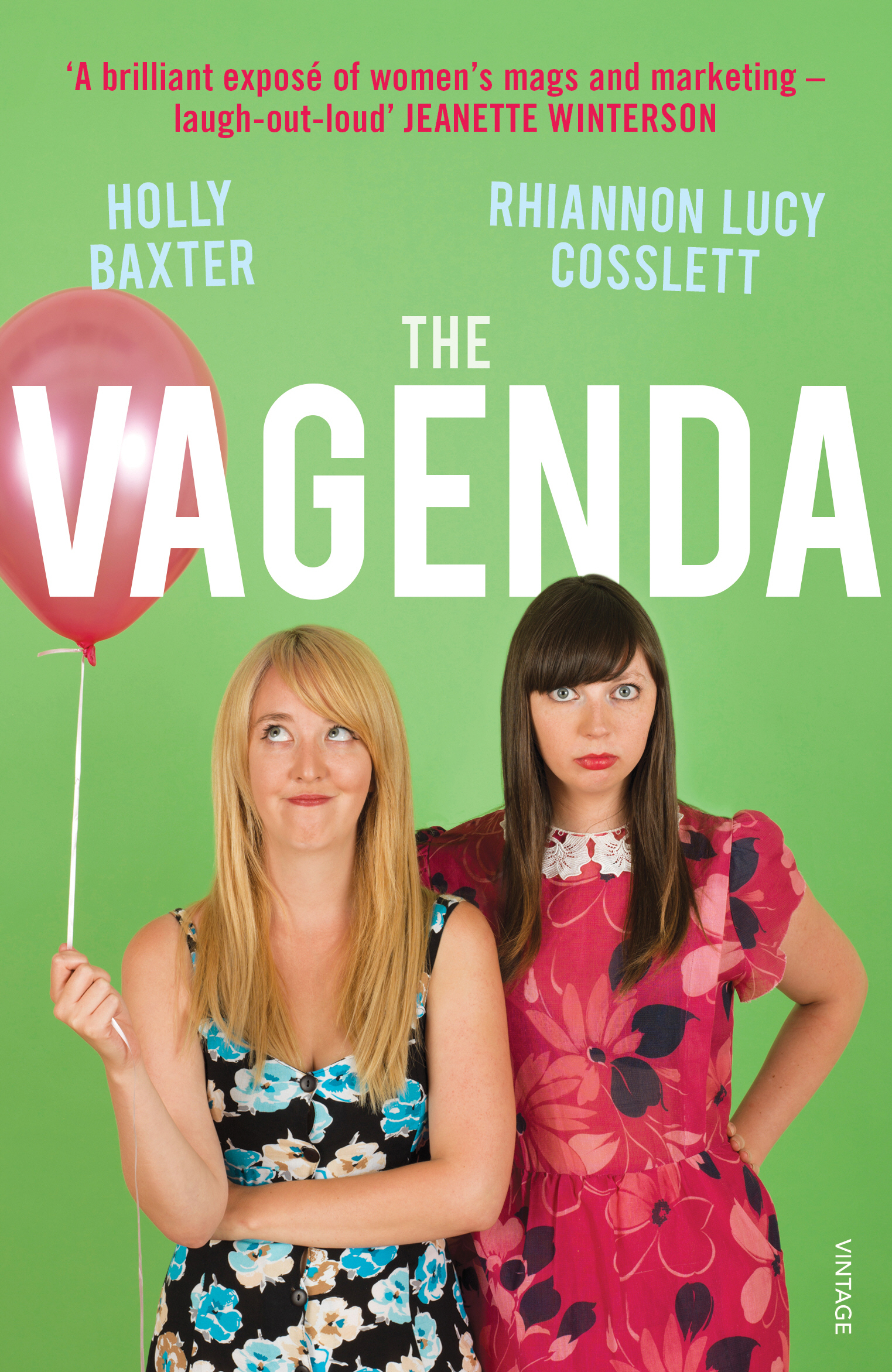

As writers of The Vagenda book, we (and from what our friends/colleagues say, young feminists in particular) have come to see being criticised by our elders as an occupational hazard when writing about women’s issues. Does feminism have a generation gap? And is that a problem?

Every generation sees things afresh and that’s a good thing. In the 1970s, younger feminists argued that feminists of the previous generation had underestimated the oppressive features of family life. After all, middle class suffragists of the Edwardian era relied on domestic servants and were rarely ground down by housework and childcare.

As a historian I think it’s important to try to understand the ideas of previous generations of feminists, and to see them in context. Equally, older feminists have to understand some of the new challenges that younger women face today.

Could you tell us a little bit about the particular ‘bad girls’ covered in the book? Who is your favourite?

I confess to having become fascinated by Queenie Gerald, a young woman involved in what we would now call the sex industry, on the eve of the first world war. Many suffragettes wanted to see her prosecuted as a procuress – luring young girls into prostitution. But I started to piece together a rather different story. She was an intelligent and stylish woman. The police were often completely flummoxed as to how to deal with her: she was thought to be so dangerously seductive that younger officers were banned from visiting her alone.

Thinking through her behaviour and predicament seriously challenged my own prejudices about ‘the sex trade’.

Of all the eras and political and cultural movements that are covered in the book, which do you think had the most profound impact on the roles of young women?

I would argue that second wave feminism – or the women’s liberation movement – had a profound impact on women’s education and aspirations. But if we extend ‘political and cultural movements’ to include the social impact of the contraceptive pill, I’d highlight that as a massively important factor.

Female fuckups are now the subject of TV shows, books and articles to the point that they now seem to be sanctioned by society (I’m thinking of HBO’s ‘Girls’, Emma Jane Unsworth’s novel ‘Animals’ and Bryony Gordon’s memoir ‘The Wrong Knickers’, all of which deal with drunken and ‘promiscuous’ behaviour.) Is this progress?

Well, I’m not going to argue that drunken and promiscuous behaviour represents progress! But young people (of both sexes) do, to some extent, learn through making mistakes. They become aware of their own limits and hopefully arrive at a clearer sense of what they want.

Who are today’s ‘girls behaving badly’? What would you say is the biggest modern challenge that they face?

‘Oversharing’ on the Internet is certainly one of the hazards. This can catch up with people later on. Hopefully something will be done about making it easier to remove unfortunate postings. And to curb trolling and abuse.